Sometimes referred to as ‘the batman of the ocean’ for their no-nonsense strategy towards saving our seas, Sea Shepherd Conservation Society is also also one of our core partner charities and the last line of defence for the critically endangered Vaquita Porpoise, the most endangered marine mammal in the world.

After three interconnecting flights and an overnight coach journey later, it’s hard to believe we are actually here. We have finally stepped aboard the world-renowned M/V Farley Mowat. Until this point we had only seen this vessel in photos, battling whaling vessels and commanding extreme ocean conservation missions around the globe.

We are accompanied by our friend and filmmaker Max Smith, the latest member of the Under the Skin team. Our mission – to document the working operations of Sea Shepherds Operation Milagro V. With a bit of luck, we will also help to remove the illegal gill nets that haunt the Sea of Cortez, trapping and suffocating countless marine animals.

We are introduced to Jack, a twenty-one year old Irish lad, second in command and lead Sea Shepherd spokesperson on board. With a mohawk, tattoos and a small metal hammerhead shark hanging from a chain around his neck, he certainly fits the profile for a leader of Sea Shepherd. His eyes are sharp, his words are eloquent and his sailing experience soon becomes clear. He is a salty character by nature who rarely leaves the vessel (even when docked), except for the occasional cigarette. Despite his young age, it is instantly apparent why he is the spokesperson for Sea Shepherd. There couldn’t be a more fitting ‘new-age’ Captain Paul Watson aboard the vessel.

We start the day with a tour of the vessel, followed by safety procedures. The crew have to be absolutely vigilant in knowing what to do if the boat is attacked. The Mexican cartel is rife in these waters, where totoaba bass (aptly known as the ‘cocaine of the sea’) can fetch thousands of dollars when sold on the black market in Asia. We were fully aware of this backstory, so it was reassuring to find armed military and police on board accompanying the crew.

We set sail early afternoon. The crew busy themselves with their tasks, each having a specific role, and we depart from the dock five minutes ahead of schedule. They certainly don’t hang around, but as soon as we leave the shore the team relaxes and with spirits high, we head out to the open ocean in the afternoon sun.

Barely five minutes pass and the control room notify us that a fin whale and calf have been spotted on the horizon. One of the crew members turns to us with a smile; “You’re in luck. You’ve brought the good weather and the whales with you today.” We let out a gasp as we witness the second-largest species on Earth (after the mighty blue whale) surface in the distance.

Shortly after, a pod of friendly dolphins pops over to say hello, swimming alongside the ship amidst the wake, whilst the crew take in this special moment. The crew’s love of marine mammals becomes instantly apparent. Dressed in black hoodies clad with the iconic skull and crossbones of the Sea Shepherd logo, we understand how these guys can be labelled as animal activists. But there is so much more than activism here. This is a crew of nature lovers. Each and every member is completely at one with the ocean, and simply happiest when out at sea.

It’s only been a few hours, and the wealth of the marine biodiversity in the Upper Gulf of California has already blown us away. We feel humbled and inspired, but at the back of our minds there is a sense of unease. These awe-inspiring sightings serve as a powerful reminder of the number of species residing in these waters that also get caught up in the ‘ghost nets’. A human can decipher between a whale calf and a totoaba bass – a gill net, however, cannot.

The crew turn back to their tasks. There is work to do.

Operation Milagro runs day and night. By day, the Captain and control room crew patrol the waters, using GPS satellite navigation to locate the gillnets dropped by the small skiffs (known as ‘pangas’). Meanwhile, the crew are on deck flaking the meticulously stacked nets that have been pulled aboard the night before, cutting off the lead weights from the nets into buckets. These are later melted down and turned into diving weights – a clever initiative that helps locals to bring in an alternative revenue to the unsustainable fishing practices that are rife in these waters.

By night, the vessel patrols the waters and tracks down illegal poachers in the Vaquita refuge, using a combination of satellite tracking and drones. The crew pull up illegal gillnets that entrap not only the Vaquita Porpoise but also rays, turtles, sharks, and countless other fish. It’s an incredibly tough job that requires coordinated teamwork and man-and-woman-power, assisted by grapple hooks.

This day-and-night operation only succeeds thanks to a seamless relationship between control room crew and deck crew, state of the art location technology, superb sailing skills, and pure hard graft. This is tough work. It’s one thing doing this for a few nights – these guys do it for months at a time.

A gillnet is a 50 – 100 metre long, indiscriminately destructive, fishing net made from transparent or green nylon. Immersed in the murky waters of the Sea of Cortez, these nets are invisible to marine creatures that come into contact with them. Once entangled, they are unable to reach the surface of the water to breathe, so suffocate and die.

Jack proposed a metaphorical scenario to us, putting the destructive power of these gill nets (which he refers to as ‘walls of death’) into context. What would happen if a farmer was to set a 100 metre-long animal trap through a rich, forested woodland in an attempt to catch a single species, such as a deer? A whole wealth of species such as wolves, songbirds, red squirrels, bears, hares, and eagles would also be caught up and sacrificed as collateral damage. It would be a public outrage.

So how then, can it be ethically feasible for these fishermen to cause so much destruction in an attempt to catch one species? If you think about it, these gill nets aren’t too far removed from the metaphorical trap set on land by a farmer. But we generally don’t think of fishing practices in this way, perhaps because we don’t witness the death and destruction located under the surface of the ocean. Out of sight, out of mind.

The sun is setting and the control tower have just located another gillnet (as if by magic) below in the ocean depths. “Right crew, look sharp!”

Gradients of orange and pink sweep the sky overhead as the crew get back into position – this time with headlamps on, in preparation for the darkness drawing in. We have a long night ahead of us.

Half an hour is spent retrieving this net. Five entangled animals. Three dead. Two alive, but their situation appears hopeless. A blood-covered ray struggles for survival as it attempts to untangle itself from the net, but with every move the nylon rope sinks deeper into its flesh. “Rays are pretty resilient. This guy has probably been trapped for a few hours.”

The onboard marine biologist assesses the ray carefully, pouring water over the wounds before releasing it back from the side of the ship. We gaze down intently, expecting it to elegantly glide to freedom of the ocean depths. However, it remains floating motionless on the surface of the sea. It doesn’t look good. We ask no questions. It’s past midnight when the crew finally retrieve the third net of the night – another two large fish caught, both dead.

We all head down below deck to gather at the kitchen quarters and are rewarded (to our delight) by a delicious vegan dinner. Veganism is deeply embedded in the values of Sea Shepherd, with animal ethics and sustainability at their heart. To keep costs to a minimum, everything is cooked on board from scratch – even their bread and butter is made at sea. The job of a Sea Shepherd chef is critical – tough physical work means a crew can tire. Good food ensures energy levels and morale are kept high.

“Net number four!” Without hesitancy, the crew clear their plates and are up on deck, pulling on deck clothes and gloves, ready to haul up another net. Always, there is work to do. We’ve been working with these guys for only three nights. They keep at it for months.

The life of a Sea Shepherd is far from glamorous, but there is something special about the team camaraderie onboard this ship. You can feel it in the air. Everyone is here for the same reasons – to save our seas. We feel humbled and privileged to be aboard.

As we finish pulling in the sixth and final net, which turned out to be three nets strung together, we take a moment to stand at the back of the vessel. The stars come out and we pause, breathe in the sea air and look up at the constellations. How different they look from this side of the world.

It is our last night, and after countless hours of hauling ropes we sail through the night back to the port of San Felipe. It is not difficult to fall asleep rocking to the sway of the ocean. Before bed we all settle in the kitchen quarters, exchanging stories of previous adventures, travels, adventures at sea and life at home. What becomes apparent to us is that every crew member not only has a story to tell, but each and every crew member has a unique skill – a skill they have dedicated to Sea Shepherd. A skill they have dedicated to the oceans.

Throughout the week, during moments above and below deck, we delve into conversations with the Sea Shepherd volunteers – each with a unique and intriguing story.

One of the crew engineers had previously worked aboard an industrial tuna vessel, trawling the oceans for endangered Bluefin Tuna. He packed it in and decided to dedicate his life and skills to Sea Shepherd to combat illegal fishing practices. Another crew member worked aboard a freighter ship, carrying cargo huge distances across various oceans. Now he is the Captain of the Sea Shepherd, navigating the M/V Mowat through Sea of Cortez to track down and retrieve the lethal gillnets with his dedicated team.

Medic, chef, sailing instructor, marine biologist, drone pilot, aerospace engineer, welder, deck hand… the list went on. It dawned on us that this tight ship is run by a crew with an amazing range of complementary skills – in effect, a team formed of multiple symbiotic relationships. This is mutualism at it’s best. It reminds us of the symbiotic relationships that have evolved in the natural world – between rays and remora fish, elephants and egrets, whales and barnacles…

Then it struck us, our biggest takeaway from the trip. Everyone can be a conservationist. You don’t have to be in conservation to be a conservationist. No matter your age, nationality, skill set, occupation… everyone and anyone can be a conservationist.

What resonated with us aboard M/V Farley Mowat wasn’t just the slick teamwork, camaraderie, shared love and appreciation of the natural world. It was that each and every crew member had a story, their own unique path to becoming a conservationist – starting from humble roots, finding their own way in the world. This was a team of passionate and like-minded people who have dedicated their lives to the conservation of our oceans, each in a unique way. Just as we have chosen to use our time and skills as designers to create positive change within the natural world, every Sea Shepherd member has chosen to use their unique set of skills to conserve the wildlife of our oceans.

This is the seed of a powerful idea. By sharing this idea with a wider audience, we hope to empower others with the belief that they can do the same – transforming their mindset from ‘small person unable to create change’ to ‘empowered conservationist that can make a real difference’. This is an idea to be shared and debated, to be allowed to drift until it takes root in people’s understanding. It’s an idea worth spreading.

We fly home just in time for Christmas. We are fortunate to be able to spend the festive period with friends and family, taking time out of work to eat, drink, laugh, and catch up with loved ones. We share our experiences aboard the vessel with Sea Shepherd, reminiscing over Christmas dinner of whale sightings, ghost nets, armed military and a crew of black-clad vegan activists. Already it all feels like a hazy dream.

On Christmas day we receive an email from the Captain of the ship. “In name of the whole crew of the Farley Mowat, we wish you merry Christmas and happy New Year. It was pleasure to have you on board and we do miss your great company.” This touching message served as a powerful reminder of hard work the crew put in day in, day out, far away from their families, to serve the voiceless animals of distant waters. Pulling nets, releasing animals, patrolling waters, and of course avoiding confrontation with the Mexican cartel.

Sea Shepherd’s Operation Milagro campaign is ultimately the last line of defence for the little Vaquita, a species heading for extinction. ‘Milagro’ is Spanish for ‘miracle’. With less than 30 of these elusive porpoises remaining, there couldn’t be a more fitting word. What’s more, it was Christmas. In our eyes, the selfless work of Sea Shepherd crews throughout the festive period is a miracle indeed.

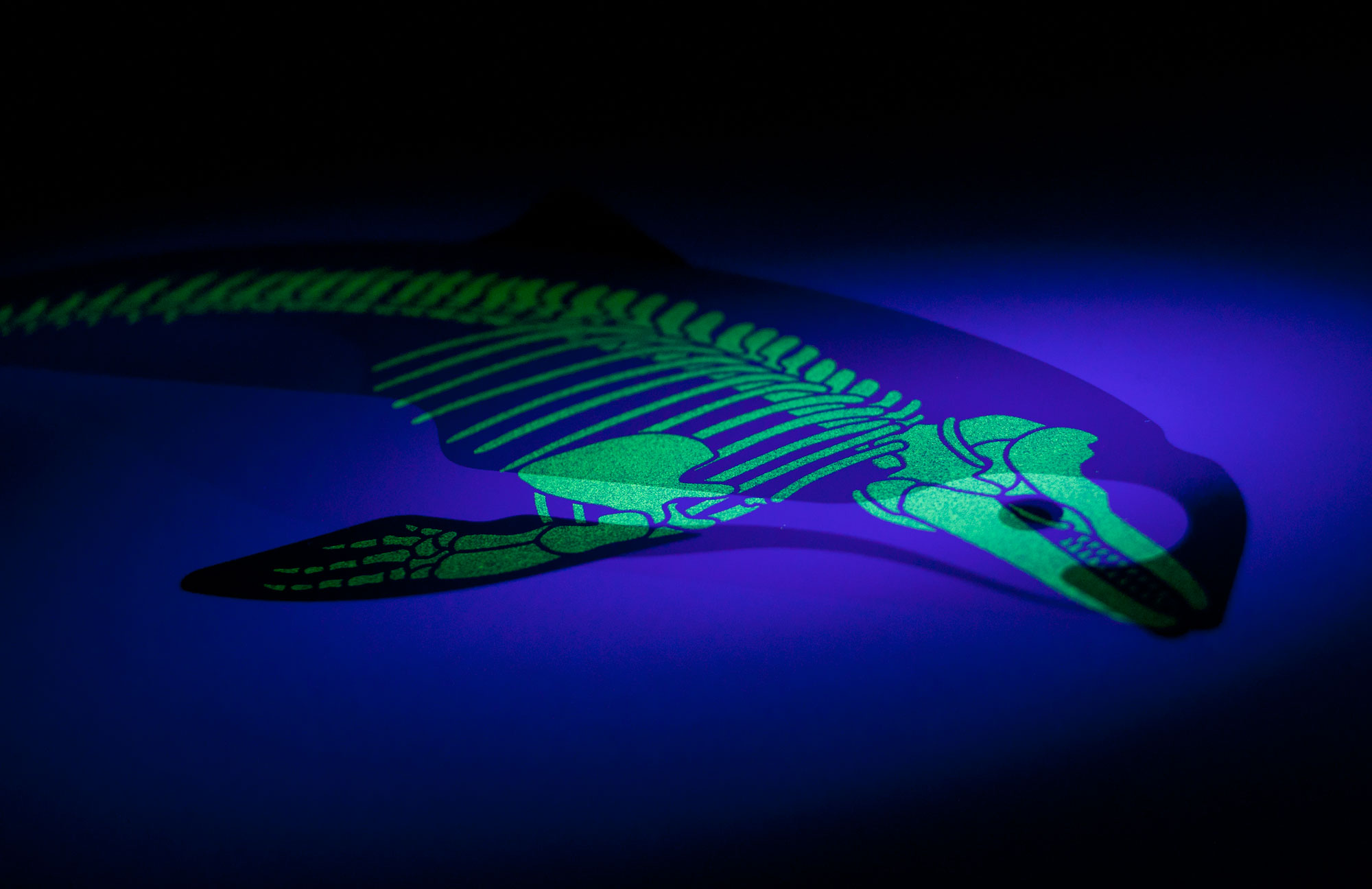

Under the Skin are proud to be collaborating with Sea Shepherd Conservation Society to create a limited edition print of the Vaquita Porpoise. 20% of proceeds go towards Operation Milagro V, their latest campaign in defence of the critically endangered animal.

Read more articles from our contributing authors and follow the project progress by signing up to the Under the Skin newsletter.