What is a porpoise? What pictures does the word evoke in your mind’s eye? When you hear “porpoise” does your brain navigate through a reel of Flipper-like dolphin images? A sleek, grey, laughing bottlenose hopping about on a jubilant tail as it skims the surface of the water? Sure, this may be an incorrect representation of a porpoise, but perhaps it is how you experience the word. Truthfully, porpoises are dolphins in as much as foxes are dogs. Dolphins, long streamlined playful cetaceans with pointed beaks are larger than their shy, round-nosed, whale-faced, barrel-bellied porpoise counterparts.

Full grown, the Vaquita is no more than 1.5 meters (5 feet) in length and weighs in around 55kgs (120 pounds). That makes the world’s smallest known cetacean approximately nana-sized. Comparatively, bottlenose dolphins can grow all the way to 4 meters (14 feet) and it is not unheard-of for them to reach weights upwards of 300 kilograms (660 pounds)! A fraction of the size and with less than half the lifespan, little Vaquitas are estimated to live a mere 20 years. It is difficult to relay much information about the habits of the Vaquita as they are still a mystery to science and, quite probably, always will be.

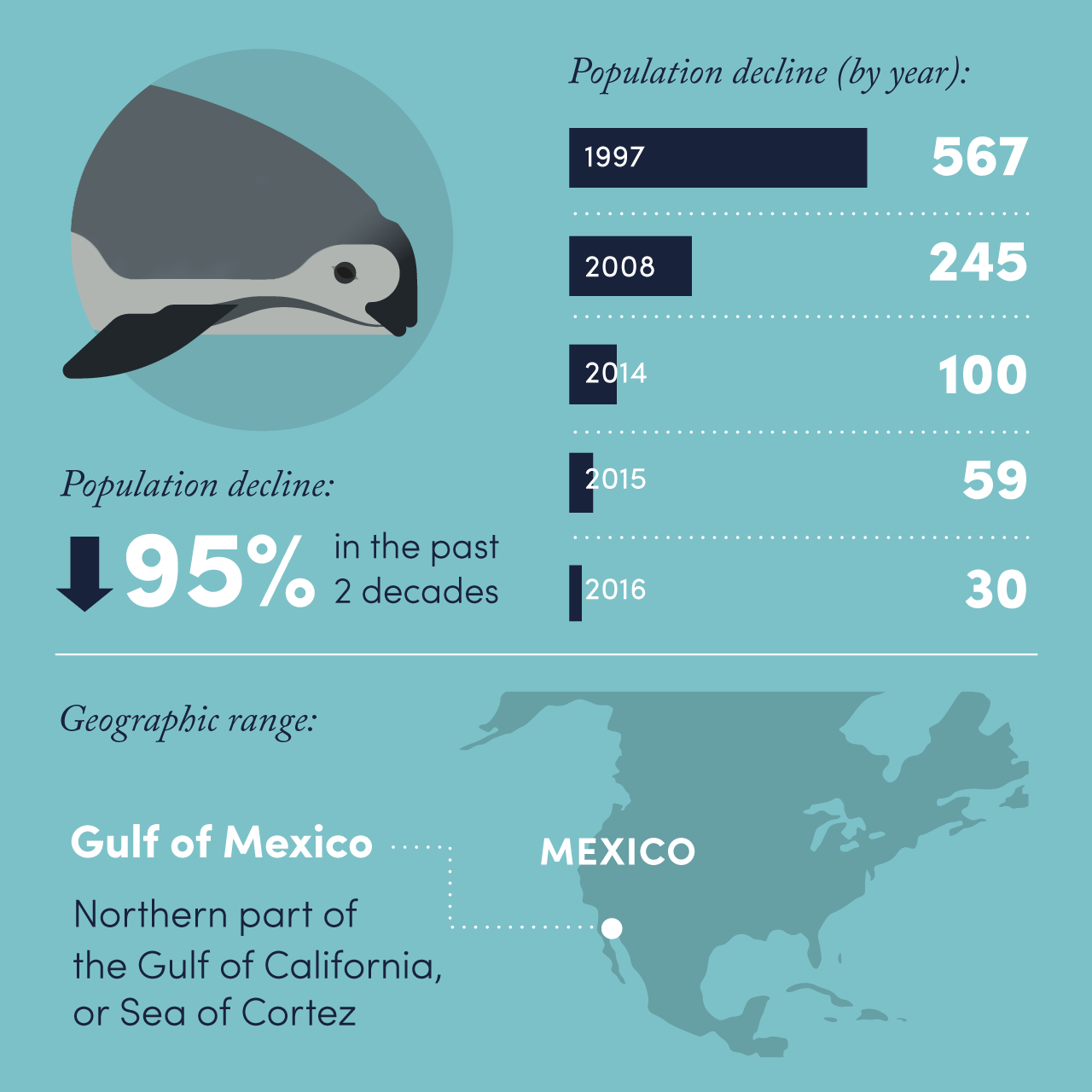

The Gulf of California is the narrow body of water which separates Mexico’s Baja Peninsula in the West from the rest of the Mexican mainland. The northernmost part of the Gulf of California is the only place on the planet where the Vaquita can be found.

Over generations, they have thrived in a small cluster – the numbers of their population supported by the limits and boundaries of their reasonably small and unique ecosystem. Literature on the number of Vaquita corpses found washed ashore in recent decades suggests that, when their population was thriving, it would have been in the hundreds.

It was 1958 when the Vaquita’s existence was first publicised to the world and it was 1996 when this little panda-eyed porpoise made it onto the critically endangered species list: a fate directly attributable to human influences. As of 2017, that population is now estimated to be a meagre 30 individuals. At present, the Vaquita isn’t just critically endangered, it is the most endangered marine animal on the planet.

So… how did this happen? How in 60 short years did we go from discovering the Vaquita to nearly obliterating it’s population out of existence? In it’s simplest form, the Vaquita is collateral damage.

The Totoaba Bass is a large unremarkable fish with which the Vaquita shares its habitat. There is nothing particularly special about the Totoaba Bass itself: it has scales and fins and gills like any other fish. Unluckily for the Totoaba Bass, it’s swim bladder is considered a delicacy in China. Unluckily for the Vaquita, it is about the same size as the Totoaba Bass. Vaquita that become trapped underwater, entangled in gill nets intended for Totoaba Bass, drown. Most of what we have learned about the Vaquita has been gathered through autopsies of those porpoises who have met their end in fishing nets. With less than 30 of these animals remaining on the planet, there is a real chance that this may be the only way we ever get to learn about them.

The question of how, 20 years after being acknowledged as critically endangered, the Vaquita’s numbers are continuing to rapidly decline remains. Why have the conservation methods implemented by the Mexican government proved completely unsuccessful?

The answer to this is rooted deeply in a complex web of social issues. From failing governmental institutions to a lack of community consultation in policy creation to extreme poverty to organised crime and the exportation of black market exotics. Totoaba poaching continues and the more endangered this fish is, the higher the price it will fetch on illegal markets. So long as those people living on the cusp of the delicate Gulf of California ecosystem lack social and economic support, the Vaquita will continue to find itself caught in the crossfire. In theory, actions have been taken to protect the Vaquita. In practice, none of these methods have aided the Vaquita’s enduring survival.

Under the Skin are proud to be partnering with Sea Shepherd Conservation Society to protect the Vaquita Porpoise. Watch the film to learn more about our collaboration in defence of this critically endangered ocean species.

During Operation Milagro III alone, Sea Shepherd removed 233 illegal fishing gear, 1195 entangled dead animals – including shark, dolphins, whales, turtles ad sea lions – and released 795 live ones. You can find out more and make a donation here https://seashepherd.org/campaigns/milagro/about-milagro-iv/

Read more articles from our contributing authors and follow the project progress by signing up to the Under the Skin newsletter.